Toohey Forest Geology

Distinct geological formations occur throughout Toohey Forest which result in variations in the soil and, in turn, differences in the vegetation. Geologically Toohey Forest is interesting because the area is where many of the elements of the geology of Brisbane converge. Some of the underlying rock strata was deposited 380 million years ago at a time when the area was deep under the ocean (Neranleigh-Fernvale series). The tough bands of quartzite are indicative of the huge forces that shaped the ancient ocean floor sediments and resulted in the mountains that we see today (e.g. Mount Gravatt, Toohey Mountain and Wellers Hill). Most of the soils found on these rocks are shallow, sub-fertile and relatively porous (i.e. do not retain moisture). These qualities ensure that dry sclerophyll forest is the dominant vegetation type in Toohey Forest.

Select species of native plant are indicators of the underlying geology. For example, Grass Trees (Xanthorrhoea johnsonii) are prolific in the sandstone areas while the Bottle Brush Grass Tree (Xanthorrhoea macronema) prefer the metamorphic rock areas of the Neranleigh-Fernvale series.

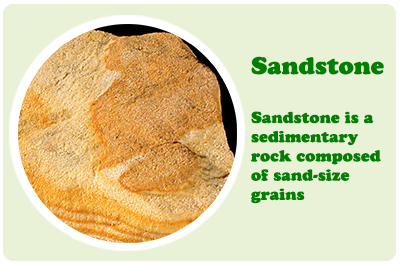

Rocky outcrops date from the Jurassic period around 200 million years ago (Woogaroo sub-group) and would have originated as freshwater sediments in inland seas and lagoons. Sandstone, shale and and conglomerates are evident from this era. Weathering has exposed the coarse sandstone outcrops and a number of small undercut caves (i.e. tafoni) and solutions pans on the surface rocks (gnamma). There are sections of more fertile red soils (Sunnybank formation) towards the south east of Toohey Forest which mask a sandstone aquifer (i.e. underground layer of water). These soils are typically deeper but prone to erosion when exposed. In the south-west of the forest there are some minor coal bands resulting from the sedimentary carbon-rich shales of the Triassic Period (Tingalpa formation/Ipswich Coal Measures).

Toohey Forest is a watershed for 3 catchments which drain into the Brisbane River: Norman Creek, Oxley Creek and Bulimba Creek.

Acknowledgement: Willmott, W & Stevens, N 2012, Rocks and Landscapes of Brisbane and Ipswich

Fossils

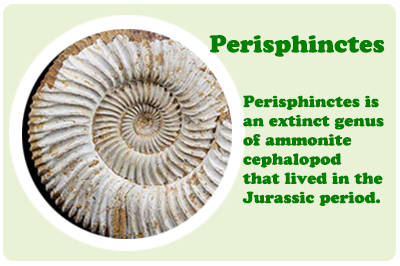

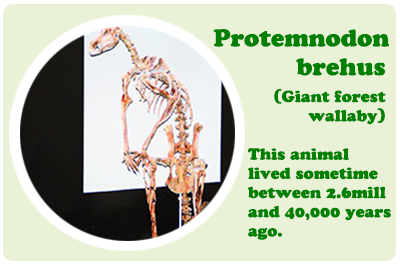

Fossils are our windows into the past. The word 'fossil' comes from the Latin word fossus, which means 'dug up'. This refers to the fact that fossils are the remains of past life preserved in rock, soil or amber. Generally, the remains were once the hard parts of an organism, such as bones and shell, although, under exceptional circumstances, soft tissue has also been fossilised. There are different types of fossils because remains can be preserved in a variety of ways. These include trace fossils, fossils with some organic material preserved, mineralised fossils and impression fossils.

Sources: http://australianmuseum.net.au/what-are-fossils

Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks are formed from the solidification of molten rock material. There are two basic types:

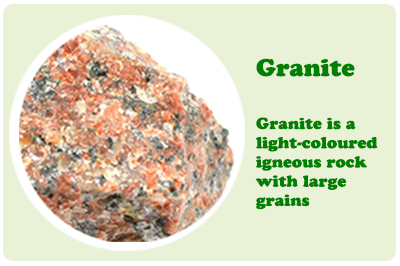

Intrusive igneous rocks crystallise below the Earth's surface, and the slow cooling that occurs there allows large crystals to form. Examples of intrusive igneous rocks are diorite, gabbro, granite, pegmatite and peridotite.

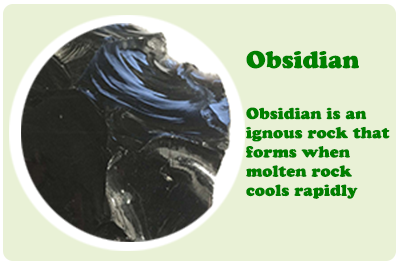

Extrusive igneous rocks erupt onto the surface, where they cool quickly to formsmall crystals. Some cool so quickly that they form an amorphus glass. These rocks include andesite, basalt, obsidian, pumice, rhyolite, scoria and tuff.

Sources: http://geology.com/rocks/igneous-rocks.shtml

Metamorphic Rocks

Metamorphic rocks have been modified by heat, pressure and chemical processes, usually while buried deep below the Earth's surface. Exposure to these extreme conditions has altered the mineralogy, texture and chemical composition of the rocks.

There are two basic types of metamorphic rocks:

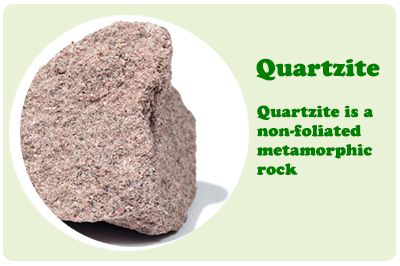

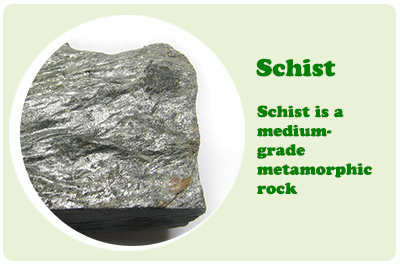

Foliated metamorphic rocks such as gneiss, phyllite, schist and slate have a layered or banded appearance that is produced by exposure to heat and directed pressure.

Non-foliated metamorphic rocks such as hornfels, marble, quartzite and novaculite do not have a layered or banded appearance.

Sources: https://geology.com/rocks/metamorphic-rocks.shtml

To meet the definition of "mineral" used by most geologists, a substance must meet five requirements:

- naturally occurring

- inorganic

- solid

- definite chemical composition

- ordered internal structure

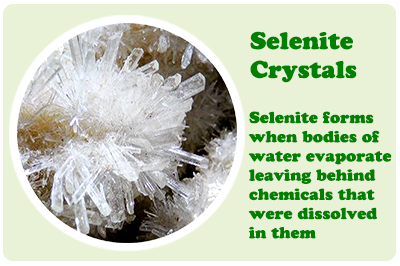

"Naturally occurring" means that people did not make it. Steel is not a mineral because it is an alloy produced by people. "Inorganic" means that the substance is not made by an organism. Wood and pearls are made by organisms and thus are not minerals. "Solid" means that it is not a liquid or a gas at standard temperature and pressure.

"Definite chemical composition" means that all occurrences of that mineral have a chemical composition that varies within a specific limited range. For example: the mineral halite (known as "rock salt" when it is mined) has a chemical composition of NaCl. It is made up of an equal number of atoms of sodium and chlorine.

Every person uses products made from minerals every day. The salt that we add to our food is the mineral halite. Antacid tablets are made from the mineral calcite. It takes many minerals to make something as simple as a wooden pencil. The "lead" is made from graphite and clay minerals, the brass band is made of copper and zinc, and the paint that colors it contains pigments and fillers made from a variety of minerals. A cell phone is made using dozens of different minerals that are sourced from mines throughout the world. The cars that we drive, the roads that we travel, the buildings that we live in, and the fertilizers used to produce our food are all made using minerals.

Source: https://geology.com/minerals/what-is-a-mineral.shtml

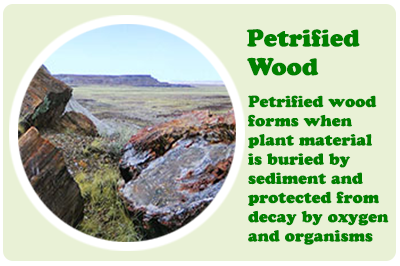

Sedimentary rock formation begins with igneous, metamorphic, or other sedimentary rocks. When these rocks are exposed at the earth’s surface they begin the long slow but relentless process of becoming sedimentary rock.

Weathering

All rocks are subject to weathering. Weathering is anything that breaks the rocks into smaller pieces or sediments. This can happen by the forces of like wind, rain, and freezing water.

Deposition

The sediments that form from these actions are often carried to other places by the wind, running water, and gravity. As these forces lose energy the sediments settle out of the air or water. As the settling takes place the rock fragments are graded by size. The larger heavier pieces settle out first. The smallest fragments travel farther and settle out last. This process of settling out is called deposition.

Erosion

The combination of weathering and movement of the resulting sediments is called erosion.

Lithification

Lithification is the changing of sediments into rock. There are two processes involved in this change. They are compaction and cementation.

Compaction

Compaction occurs after the sediments have been deposited. The weight of the sediments squeezes the particles together. As more and more sediments are deposited the weight on the sediments below increases. Waterborne sediments become so tightly squeezed together that most of the water is pushed out. Cementation happens as dissolved minerals become deposited in the spaces between the sediments. These minerals act as glue or cement to bind the sediments together.

The process of sedimentary rock formation takes millions of years to complete only to begin a new cycle of rock formation.

Source: https://www.rocksandminerals4u.com/sedimentary_rock_formation.html